Fattoush

some big thoughts, a couple of links. go carefully with your hearts!

Listen: we live in a post-Ottolenghi world.

If you are reading this newsletter, you almost certainly live in a post-Ottolenghi world.

There is tahini in the cupboard and hummus in the baby food aisle and pomegranate molasses has gone in and out and back again. We all know our way around a lemon; we all know our way around a chickpea. The rise of the bountiful salad! The rise of the swipe of sauce, tahini-laden, and the scatter of pine-nuts! Cardamom! Pistachio, sound of the summer! Mint! Coriander! Sesame seeds! Za’atar, sumac, cucumbers not boiled in cream a la E. David (and indeed Monty Don) but sliced and tossed with ripe tomatoes and white cheese and honey and olives and olive oil, gallons of it, green and gold and glistening. Pitta bread, for god’s sake. It’s Ottolenghi’s world and we’re just living in it. You cannot get away from the man! You cannot open a cookbook without seeing his strong and beautiful influence! You can scarcely open a middle-class cupboard in this city! And now it is summer. It is peak joyful Ottolenghi season. It is time for hummus and beetroot dip and barbecues and shawarma and falafel and fattoush. These are the things I make in summer and the things I want in summer.

The other evening I was making a fattoush: buying big bunches of herbs at the World Food Centre, frying the small khobez in olive oil to make chips, cutting up the big tomatoes and the little cucumbers, eating olives from the tub while I was turning the chips over in the pan. I shook the sumac up with lemon juice and cider vinegar and more oil; I sprinkled the chips with salt, long thin ribbons of crisp golden khobez all tangled up with each other like a sculpture, and dipped the fattest one in the tahini to sustain me until dinner. I was listening to Warren Zevon; I was alone in the kitchen; there were sunflowers on the table.

It was impossible not to think about Gaza.

It is always impossible, lately, not to think about Gaza but it is most pressing for me when I am cooking; when I am cooking in my post-Ottolenghi kitchen, when I am cooking with the ingredients of the Middle East, which are the ingredients of my own kitchen– sesame, tahini, olive oil, greens, tomatoes– when I am cooking from Jerusalem, which is a book I have always loved, which Ottolenghi wrote with Sami Tamimi. Ottolenghi is Israeli and Tamimi is Palestinian and I can’t now even begin to imagine what that cookbook, this celebration of what is shared between the people who have lived in this place, this celebration of what can go between and what was then not lost, feels like to either of them. How do you look back on your work that was full of hope and effort and thought when between you and it are so many bodies? I will not try to imagine how it feels because I think I would be inadequate to the task; or in fact I will try to imagine it but I will not try to write it down. I will not try to write this down.

It’s not that I’m not thinking about the starving while eating cottage pie; it’s not that there are no other kinds of famine; it’s not that this is the only monstrous thing in the world. Not at all! It’s so bad in so many places! It’s just that in a post-Ottolenghi kitchen, I’m reaching for tahini; I’m shopping for flatbreads at the Arabic supermarket; I’m buying lemons and olive oil and chard and white beans. I am making fattoush without even thinking about it. The flavours of Palestine are the flavours of the Middle East are the flavours of the middle-class Londoner, maybe even the flavours of everywhere now but I am trying so hard to speak only for myself and nobody else. The flavours of Ottolenghi are the flavours of Israel which are in many ways the flavours of Palestine, also the flavours of Lebanon, Turkiye, all the way down through Greece. There are no hard boundaries in food: now less than ever.

It is impossible to cook anything or eat anything– lemons, mint, lentils– without thinking about Gaza.

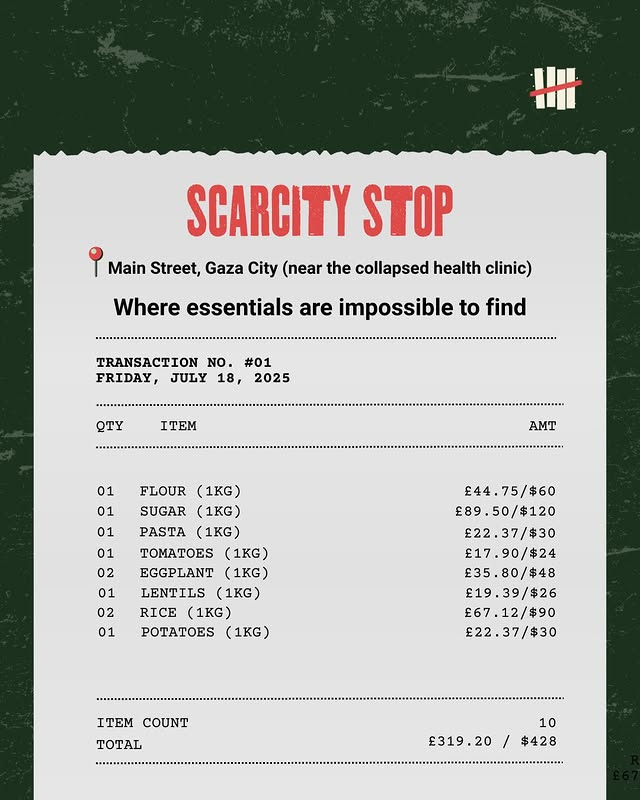

It is impossible to be adequately grateful for this thing– this fresh good thing, this kitchen, this safe life. It is impossible to be adequately grateful for this thing that should be a right: this thing that should be possible for all people, and is not. It has been made not possible. It has been dressed up as impossible. The World Food Programme has enough food to feed the entire population of 2.2 million Gazans for two months – within and on its way to the region. They don’t think they can get it in. They don’t think they can get the food to the people who need it. It’s there and it’s not there. What can you do with a statement like that?

I can’t write about this. I am not skilled enough to write about what’s happening and what’s happening and what’s happening. I can only write about food and how I feel: this is all I have.

I see these videos, sometimes, of women– mostly women– holding their bone-thin spindle-wrist children up to the camera, being clearly and articulately grateful for the pastes and powders that the charities can smuggle in. I see their unsmiling faces as they express that the thick syrup of peanut powder and evaporated milk has saved their child for one more day. I see these people who had homes and kitchens and lemons. I see these people who were made for joy in the way all people were made for joy and I hate to see them be grateful for something so far from what was supposed to be, what could be, what should be. I know why these videos are made. I click through; I make my donation. I still hate it. I would hate it if I were them. I would feel– again I will not try to imagine how it feels because I think I would be inadequate to the task; or in fact I will try to imagine it but I will not try to write it down. I will not try to write this down either.

I go to the international supermarket and I walk past all the Free Palestine flags hanging from all the windows and I buy lemons and coriander and mint and the small tiny spiny cucumbers I love because they are just a little bitter.

The things I am eating are the things that they are not eating: this is the very plain truth. I can write about food without writing about Gaza but I can’t write about food without thinking about Gaza. I can say this or not say it but either way it remains true.

Everywhere on Instagram it’s summer and it’s an Ottolenghi summer, as every summer is in middle-class London. It’s beans and dips and swirls and drizzles. Everywhere I look it seems there are small plates and tomato salads and beaches and cool clean water. Everywhere there are little small tiny spiny cucumbers and bunches of mint and greens and baby-heavy bags of lentils and dried beans. Everywhere there are the big tins of olive oil. Everywhere there are olives and clay-soft avocados and soft pittas. Everywhere here, nowhere there. I can’t write about food without thinking about Gaza. These ingredients are their ingredients. These things are here and they are not there. It is impossible to write about food without thinking about Gaza. It is impossible not to write about food; it is my job and my joy. It is impossible not to think about Gaza. I don’t want not to think about Gaza. I don’t want to look away even as looking feels as impossible, as intrusive, as ignoring.

I would want– I would not want– I will stop trying to speak for people and speak only for myself: when I read about food, when I write about food, when I cook, when I eat, when I wash up with clean drinkable potable water, when I run the tap to get it hot or run the tap to get it cold– it is impossible to be grateful enough, to be horrified enough, to be open enough to the vast suffering of the people of Gaza at this time. It is impossible to understand it. It is impossible to come to terms with the fact that it is happening and it is still happening and it is real and happening now as I am writing. It is happening now as you are reading. The food we are eating and not eating is the same food. There is a connection and there is a debt.

World Central Kitchen were cooking in Gaza until four days ago, when they ran out of ingredients. They are baking bread still and cleaning water. I have donated here and wish I could give more.

More directly, this fundraiser was shared by a friend of a friend a year ago. Nothing has changed except that everything is worse now. I believe that they are doing good work. They say that there is some food still there and that they have a plan to get it to people: buying direct from the sellers, so that the sellers don’t have to try to sell food in a famine. This is their GoFundMe and I have given here too, and again I wish I could give more. Someone said to me, don’t you wonder who the merchants are, and why the prices are so high? And I do wonder that. I wonder that and I know what she’s getting at and I know why she said it and I don’t disagree, necessarily, but what is the alternative? Some people I know are giving cash directly to Gazan people they have met on Instagram, and I get a lot of requests for cash directly, as I am sure most people on Instagram do, and I can’t speak to that either but to be asked directly for aid by someone desperate is hard, hard, to refuse.

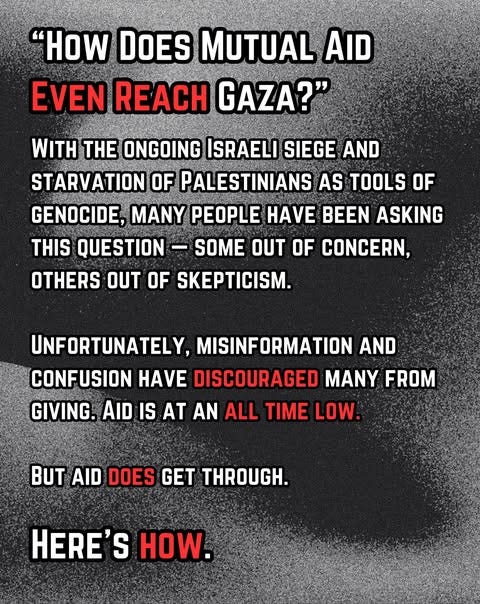

This link (embedded above) was helpful to me in thinking this through. I don’t know these people at all but these slides were helpful to me, and maybe to you.

There are big charities, but you know about them. I give to them too.

Sami Tamimi’s latest book is called Boustany and it’s about vegetarian recipes of Palestine. You can read about it here. It’s a really beautiful interview and you should click through (and buy the book also).

“Palestinian people are full of life, they always want to make you welcome and will push food on your plate just to make sure that you are well fed, happy and comfortable,” Tamimi said. “It’s horrendous for people that always celebrated life and food and seasonality and feeding people to be stripped from all of that, and for it to be used as a weapon against them….They want to eat and enjoy life, they want to live life to the max.”

I love to enjoy life. I love to eat. I love to cook and feed people and be in my kitchen, wherever that kitchen is.

And there is such joy in food! There is such joy in good food; in clean cold water; in lemons and extravagance and green-golden olive oil. I break the white cheese and put sumac over it. I pit the olives and tear the soft bread. I make rice and breathe in the steam. I blitz beans. I find all this joy and I find in my own joy such total horror and bitterness I don’t know what to do. I don’t know what to do. I donate; I write; I write and write and write. I cook and I write and I think.

I am writing this now because of the fattoush, and because I recently went back on Instagram for work purposes, and shared the links above. It seemed to be helpful to share the link here too, and once I started writing I couldn’t stop. It’s important for me to say very clearly that I don’t know anything about anything. I can’t verify fundraisers or fix intransigent global conflicts or free hostages or unlock the prisons and let the people go. I don’t know anything about how things work, just about food and feelings, and to be a food writer in a famine— tahini, lemons, lentils— is a strange place to make a living and a life.

I don’t know what the good ending to this story is. I don’t know what the right answers are to world wars and climate change and kidnap and murder and fascism in all forms. I don’t know what to write; I don’t know what to say. I see protests in Tel Aviv and hunger strikes in London (sponsorship to here, please) and all over the world I see people who want this to end. I clicked through to this Etgar Keret Substack yesterday and it made me feel— not hopeful, of course not, what hope could there be? But like there are people everywhere who want this to end, who see what’s happening, who want this over. I saw the front page of the Daily Express— GAZA HELL SHAMES US ALL— and I felt it then too. These people I think of as far from me: on this, at this time, we are aligned. Daily Express readers; and 80% (if that Keret piece is right) of Israeli citizens; the protests everywhere, all the time. There are people everywhere who see this. There are people everywhere from all places who see what is happening and want it to end.

And still it does not end. I am not naive enough to think that writing about this on a Substack means anything at all, or will change anything, but there are links here that you can give money to; and also, a little off-topic but perhaps useful for the feeling that one gets when looking at Palestine and the Congo and Sudan and everywhere else where the world is too raw to bear easily—

Anyway, listen, I urge you to as well as donating and writing and protesting and striking and anything else you can think of doing, check in with the people in your own community. This is the only real route out of global despair I know: doing something. And if you are too far away to do something there, you have to do something here. If you are feeling hopeless and far away, find something close and practical to do. Deadhead flowers in the community garden. Work shifts at the community library. Take care of someone’s kid so that they can use their skills to make something move somewhere else. Call your grandmother. Talk to your neighbours. Talk to people, talk to each other. Don’t write people off. Write to your MP, not that it ever seems to move the needle. Write about it. Write about everything. Cook about everything. Exist with as much joy as you can; reach out to everyone you can; give everything you can wherever you can. This will not help globally. It will only help locally. But then the globe is just made up of small locations one after another, and we are all connected in ways that are both apparent and not yet apparent, ways that will only become more visible the more things fall apart. We will need those connections, I think, in time. We need them already. We need them now.

***

Thank you very much to the people who read this piece in draft. This newsletter is always edited by somebody, but this time I pulled in the full gang of big thinkers. I really appreciate your willingness to read with rigour, to bring your personal experiences and smartest thinking to make hard subjects worth writing about. Thank you for your time and care.